How central banks, markets and investors got interest rates (and inflation) so wrong – and what that means for investors.

The ‘Uber Test’ (once the ‘Taxi Test’) is a simple gauge of sentiment. The topic of conversation is a microcosm for what society is thinking about.

Right now, there’s probably a good chance you (or your Uber driver) will be saying: my mortgage is going up so much it’s scary! (interest rates), or the cost of fuel and lettuce is ridiculous! (inflation). My Robinhood portfolio is way in the red! Bitcoin’s down another 20%! (rising interest rates ending the era of easy money and putting pressure on asset prices).

Interest rates are the topic du jour, and everybody seems to have a view. Especially after another 50bps increase in the Cash Rate at recent 5 July RBA Board meeting, the fastest rate tightening on record,1 with the RBA saying it “expects to take further steps in the process of normalising monetary conditions in Australia over the months ahead".2

Beyond Ubers, headlines in the financial press are dominated by well credentialed ‘experts’ spouting bold claims about how they had crystal-balled this precise scenario. They knew inflation wasn’t transitory and rates would rise aggressively, exactly on the current trajectory. And now they are ready to tell you precisely where rates will go from here and what you should do with your money.

Don’t count on it. Most people making these claims are engaging in revisionist history. They didn’t really know how interest rates would evolve or what comes next.

Truth is, neither did we. No one knows what is going to happen tomorrow. The wonderful thing is that to invest well you don’t need to be a clairvoyant. You just need to focus on a simple, seldom-asked question. And it’s not ‘What’s going to happen tomorrow?’ but rather ‘What do I have to believe for this investment to make sense?’.

The difference is not semantics. It’s profound.

Let us explain.

How wrong the experts and the market got it

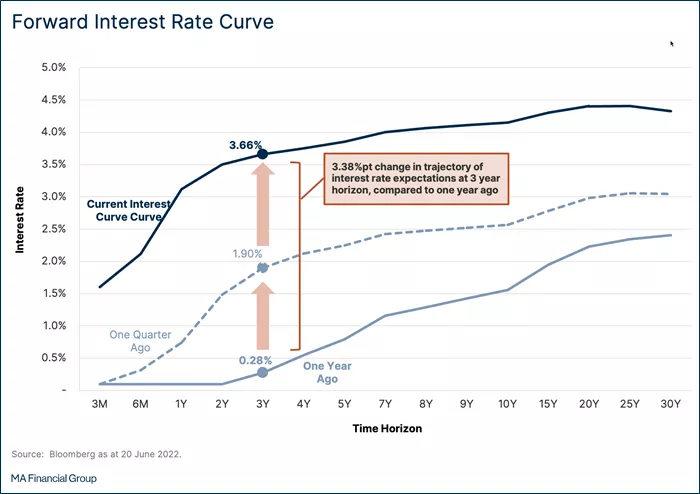

One year ago, the market’s expectation for future interest rates in Australia was for very slow and gradual changes from the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) emergency settings during the COVID-19 pandemic. The three-year outlook was for rates of only 0.3% by 2024.

At one point in September 2021, amid the COVID-19 delta strain lockdowns, the market started to price in moderate increases in the RBA cash rate. And very moderate indeed: 0.25% by the end of 2022, 0.6% in 2023, and just 1% in 2024.

These (small) market moves ruffled the RBA’s Governor, Dr Philip Lowe, so much he moved to emphatically dismiss them in a public speech that same month: “These expectations are difficult to reconcile with the [challenged economic] picture I just outlined, and I find it difficult to understand why rate rises are being priced in next year or early 2023,” Dr Lowe said.3

That’s not to pick on our central bank. Global policy makers all made similar pronouncements. The experts concurred (even many of those now revising history). Most of the world’s leading economic forecasters in a Wall Street Journal survey last July said they believed inflation would end 2022 below 2%, supporting low and gradual interest rate increases (and that was after several high, but allegedly ‘transitory’, inflation readings).

Investors listened and priced assets based on these same expectations.

What a difference a few months makes

Financial markets and astrologers forecasters are now pricing in steep interest rate rises towards the 3% to 3.5% level within the next year or two.

Central bank rhetoric is to brace for rapid rate rises towards historically normalised levels (whatever that means).

You can see this visually below. The forward interest rate curve has dramatically shifted upwards from one year ago and one quarter ago.

If current consensus is right, last year’s consensus was so badly wrong it was an entirely meaningless basis for making any decisions.

That's a big problem given lots of people made decisions based on that view of the world.

It is why global equity markets have sold off as much as 30% in 2022 and even bonds, traditionally considered a safe-haven, are down 15% in their worst year to date performance in over 30 years.

How could this happen? The problem with the GFC playbook

Central bankers, economists, investors – even market fortune tellers – are just human. Humans suffer from bounded rationality; your mind gravitates to the tunnel vision of what you have observed in recent experience.

Central banks, it seems, were fighting the last war. They were using the playbook written after the global financial crisis of 2008, when inaction (not too much action) was the risk, when growth and inflation remained stubbornly below target bands, and wages were sluggish.

Policy makers’ models were calibrated for a financial crisis, not a health crisis. They couldn’t rationalise how well-intentioned stimulus to save businesses and employees from forced shutdowns would change the composition of spending from services to goods and how that would impact inflation, nor how those lockdowns would create supply-chain pressures that fuel price growth.

They also didn’t seem to contemplate the wealth effect of record-low interest rates accelerating asset prices and supporting robust consumption from people who now felt richer.

This caused the leading minds in monetary policy to dogmatically stand by forecasts embedded in firm time horizons (like, “no interest rate rises before 2024”) – even when the facts were changing.

Why investors need to ignore forecasts

Nobody knows where interest rates will be in two, three, five or 10 years’ time, with any degree of accuracy.

In fact, trying to predict guess the future for interest rates (or any other economic metric) is not only unnecessary to make good investments, it’s outright dangerous.

It causes an investor to calibrate their portfolio only for one scenario — such as 3-3.5% base interest rates within two years — based on a single view that is just one of a wide range of possible outcomes.

What if your chosen guess (probably, the prevailing consensus) is wildly wrong? That’s what happened to markets and central banks last year — and it’s not ending well.

A more rigorous investing approach: Knowing ‘What You Have To Believe’

In our view, the most rigorous approach to investing is built around a simple, but seldom asked question: What do I have to believe for this investment to make sense?

There is little point trying to guess specific inputs to intricate financial models. It squanders the benefit of (hopefully extensive) research about an investment, by formulating a static view of the world upon which you rely — such as, here’s my base case, upside case and downside scenario.

The ‘What You Have To Believe’ framework focuses on understanding how an asset or portfolio behaves in the real world across a spectrum of possible outcomes.

There are no fixed predictions or forecasts. Instead, the focus is on what conditions need to exist for the investment to succeed or fail.

This allows us to make an informed judgement about whether those conditions are currently prevailing (or not), have frequently prevailed in the past (or are rare), and whether they show signs of changing (or what would need to happen for them to change).

Most importantly, it means we are constantly looking for conditions that might undermine our thesis, testing and re-testing in real time, and have mentally prepared for what to do if that occurs.

‘What You Have To Believe’ about interest rates

The ‘What You Have To Believe’ framework can be applied to interest rates.

While we can’t predict rates, we can assess the type of conditions that would need to prevail for different interest rate pathways to occur.

There are plausible scenarios where interest rates are at the consensus, or much higher, or much lower, than the market implies over the next few years.

Here are a few examples.

The forward curve: the happy smooth landing

A goldilocks scenario. Central banks raise interest rates swiftly. Consumers react early, adjusting their purchasing behaviour. Slowing demand for goods and services naturally helps to offset high inflation, bringing price growth back under control.

Supply chain pressures abate as production resumes in core manufacturing hubs and international trade resumes after pandemic-induced shutdowns. With controlled inflation, business margins do not suffer undue pressure and employment conditions stay healthy. Immigration helps keep wage growth sensible and alleviate staff shortages, further supporting business confidence. Other externalities, like energy price shocks, are managed through recalibration of energy supplies, localisation of production and use of effective substitutes. Economic growth and inflation come back into check.

Not too hot, not too cold. Just right.

Much higher rates than the market implies: going nowhere, or the roaring (20)20’s

It’s too late. There’s no growth in the economy. Business sentiment is hammered as margin pressures created by inflation, record levels of supply chain pressure and tight employment conditions driving wage growth. Deflating asset prices, caused by the velocity of interest rate resets, impact the propensity for new investment activity. Inflation, being supply-side (not demand-side) driven, doesn’t go away in core segments like energy, housing and basic goods. Consumers redirect more of their income to meet these basic needs and service debt at higher costs, with weak discretionary spending also weighing on growth. Central banks use more of the only lever they have, pushing rates much higher to contain inflation. We enter a period of stagflation.

Or maybe it’s the opposite. There is so much cash on the side-lines, in consumer bank accounts or business coffers (saved during the pandemic), that is unleashed now the world is back open. Consumers keep spending, buoyed by robust employment conditions, creating a spending cycle that drives inflation irrespective of supply-side dynamics. Rates have to rise faster than we think to contain the situation. 3-4% benchmark rates are not enough to contain the new roaring (20)20’s.

Much lower rates than the market implies: the crash landing

No one expected this. With the market having operated for nearly two years under the (now incorrect) assumption that interest rates would stay lower for longer, the pace of rising rates causes asset prices to collapse.

Consumers struggle under higher rates with rampant inflation, drastically cutting back on discretionary spending. Some people are unable to service their loans while also funding their core costs of living, which causes defaults and a spike in bad debts. This flows into the business sector, with companies facing a disastrous cocktail of weak demand and an inability to pass on supply-driven cost pressures and higher wages in a tight employment market through higher prices. They caught with excess inventories and declining earnings, being forced to downsize.

It's heavy turbulence and a crash landing is on the horizon. The economy enters a recession. In a recession, policy makers hit the ‘break emergency glass’ button. Monetary and fiscal policy focuses on slowing the economic downturn. Interest rates have gone too far and need to be reduced again to kickstart the economy back out of recession.

Don’t believe. Know what you have to believe

These scenarios aren’t exhaustive.

We don’t know which (or if any) of these scenarios come to fruition. The important thing is we try not to guess.

Instead, we think about the conditions that could occur for different rate scenarios to prevail, and how our investment portfolios would perform in those environments. Are our investments calibrated only for a goldilocks scenario or are they resilient enough to perform acceptably in a wider set of conditions?

For us, what matters is knowing what we have to believe for each investment, and our portfolios overall, to succeed or fail.

- John Kenneth Galbraith

Please get in touch to arrange a discussion, and to learn more about our credit capabilities.